- Amazonia plays a fundamental role in the region’s economy and ecosystems, but it faces serious environmental, development, and growth challenges that make up a true Amazonian trilemma.

- That is why exploring the map of this triple challenge is so important; it reveals uneven patterns across Amazonia and underscores the need to better coordinate efforts and strengthen capacities.

- In this scenario, it is urgent to seize the window of opportunity presented by this complex trilemma to move toward integrated responses and a future of prosperity and resilience.

Every minute, Amazonia loses forest equivalent to two football fields. We often read or hear figures like this, firmly grounded in evidence. However, the environmental degradation of this vital region is too often portrayed as a fatal and isolated issue, detached from human and economic development challenges, while environmental action is commonly presented as being at odds with development itself. The reality of the Amazonian region tells a different story: economic growth, environmental protection, and human wellbeing go hand in hand.

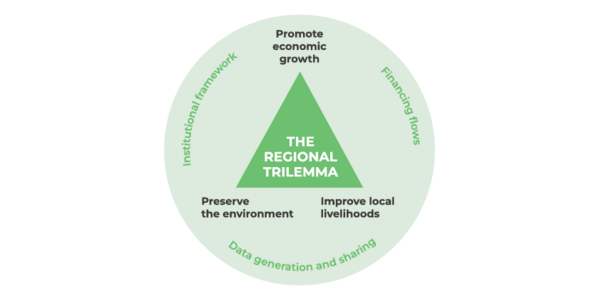

Our latest publication brings together evidence showing how economic growth, environmental preservation, and improved livelihoods in Amazonia cannot be pursued separately. They are too deeply intertwined. We are facing a true Amazonian trilemma, with far-reaching implications, since what happens in Amazonia will shape biodiversity outcomes, environmental systems, and the lives of millions of people across South America and the world.

Despite its complexity, this trilemma (Figure 1) opens a window of opportunity for integrated, cross-sector approaches that can deliver lasting results for the region and the planet.

By some estimates, 70% of South America’s GDP is generated in areas that receive water from the Amazon forest. Yet Amazonia’s own economic contribution is limited by low diversification and poor connectivity. Amazonia’s economy is heavily reliant on agriculture and mining, sectors that place significant demands on natural resources. Infrastructure gaps further limit growth. For example, in Colombia, Amazonia contributes less than 1% of the country’s GDP.

The environmental side of the trilemma is stark. Amazonia stores 120 billion metric tons of carbon and harbors 30% of the world’s biodiversity. Yet between 2001 and 2024, Amazonia lost 67 million hectares of forest—an area about the size of Paraguay and Ecuador combined. Environmental degradation, driven by deforestation, mining, and other exploitative practices, is undermining this natural capital and placing the Amazon Basin under increasing environmental strain. Over time, the rainforest could lose its ability to sustain itself, depriving the planet of a crucial climate regulator.

On the social side, Amazonia is home to more than 47.4 million people, including 379 Indigenous groups and other ethnicities, and more than 240 languages are spoken in the region. Many ethnic groups possess intricate knowledge of the rainforest and its resources, which are key to fighting deforestation and implementing sustainable development. Yet these groups face higher poverty rates and lower access to basic services.

For example, only 39% of Amerindian households in Guyana have improved water and sanitation, compared to 95% nationally. The estimated poverty rate in Amazonia is 37%, 6.6 percentage points higher than the average across Amazonian countries. This rate is even higher in some rural and ethnic communities.

Moreover, the challenges faced in the region are not evenly distributed. Overall, an estimated 661,000 people in the region live in areas that severely lack economic opportunities; over 760,000 people live in areas with severe gaps in environmental conservation, and almost 6 million people live in areas with high human development needs (see Figure 2. Economic Well-Being).

Our study finds that environmental conservation gaps are concentrated in central areas, particularly around the Amazon River and the Brazil-Bolivia border (see Figure 3. Environmental Conservation). As for economic and human development gaps, they are more prevalent in the southeast and north of the region (see Figure 4. Human Development).

The good news is that Amazonia’s trilemma can be addressed, and policies can be promoted to support its intertwined triple goals. However, this will be costly and will require greater coordination efforts among all actors working in the region.

Maintaining 80% of the Brazilian Amazon under protection, for example, would cost $1.7–2.8 billion per year. Closing all development gaps presented in Figure 2 and Figure 4 would require trillions. The scale of these requirements dwarfs current investments.

Amazonia’s institutional landscape is also complex and fragmented, often resulting in duplications and reduced impact of actors’ work. For example, there are 99 first-level subnational administrative units and more than 1,500 second-level administrative units.

The Amazon Cooperation Treaty Organization provides a platform for regional dialogue, but its non-binding nature remains a key limitation. National and subnational coordination mechanisms exist, but duplication and inefficiency are common. Better coordination and capacity-building are urgently needed.

So, what can be done about it? Our findings point to four key levers to face the region’s trilemma:

1. Strengthen environmental protection by expanding and enforcing protected areas, integrating Indigenous knowledge, and investing in climate adaptation for vulnerable populations.

2. Promote human development by improving access to education, health, water, sanitation, and transport, especially for vulnerable and marginalized groups, and tailoring solutions to rural and urban needs.

3. Foster economic growth by investing in innovation, connectivity, and finance, and supporting research and entrepreneurship that align with sustainable development.

4. Support greater trust, co-creation and coordination among all actors working in the region. To reduce duplication and enhance the impact of policymaking, underlying strategies are required. These include institutional strengthening, reinforcing processes and mandates, providing clear rules, and better use of data for evidence-based policymaking. Initiatives such as the IDB Amazonia Forever regional program support this necessity for joint answers from the countries to common challenges.

The evidence is clear: piecemeal approaches won’t work. Only by addressing economic, environmental, and social challenges together can we avoid further deterioration and move toward a future of shared prosperity and resilience.

Keywords:

Economic Analysis