- Support depends on how the information is framed, with important implications on public policies

Latin Americans back more trade by big margins, though an innovative experiment finds support is fragile and may be swayed by information emphasizing negative consequences, according to a study by the Inter-American Development Bank.

The innovative experiment to understand how perceptions of trade are affected by the way the issue is framed trade is part of the upcoming special report on trade and integration to be released in November – Trading Promises for Results – What Global Integration Can Do For Latin America and the Caribbean.

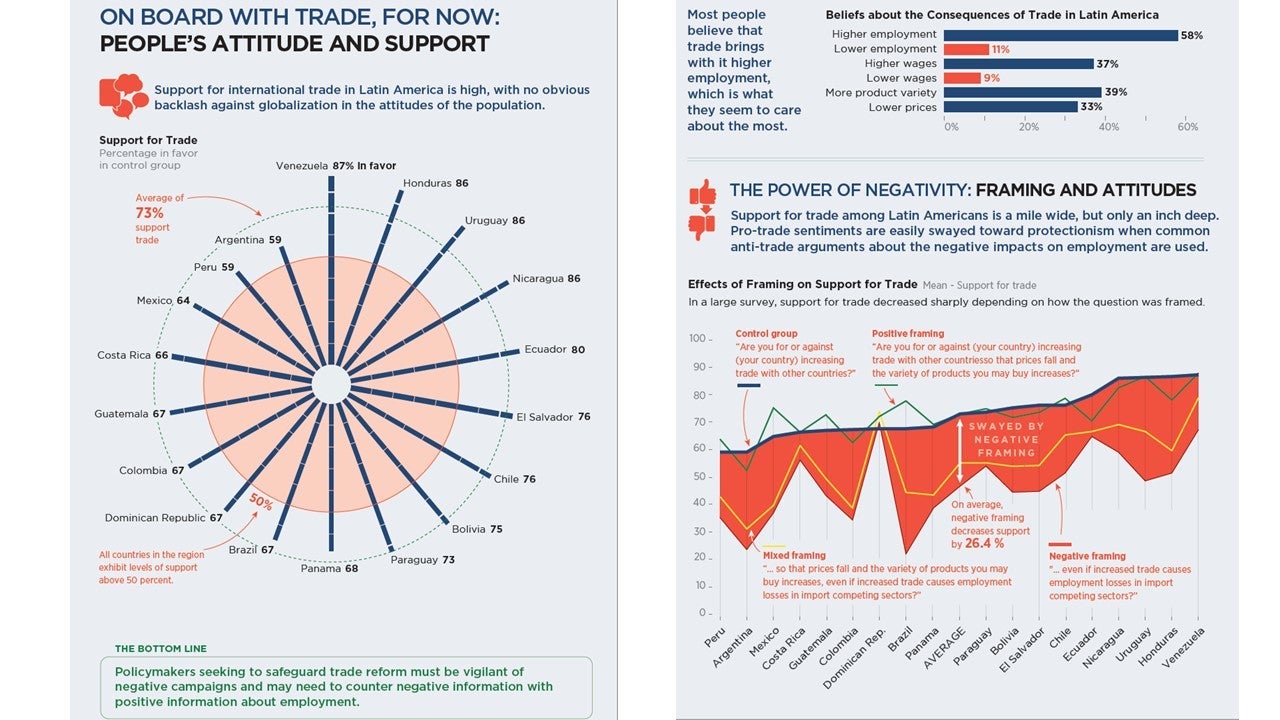

Almost three out of every four people said they favored increasing trade with other countries, with support running highest in Venezuela, Honduras and Uruguay. The study, based on a new set of questions the IDB included in an opinion survey conducted in 2018 by the Latinobarometro polling firm, found that support for trade has remained constant in most countries over the years, slipping only during times of acute crises. Almost six out of every ten Latin Americans equate trade with more jobs, with only 11 percent believing that trade means fewer jobs, and just 9 percent say it depresses wages.

Positive vs. negative information

Trading Promises for Results looks at how sensitive Latin Americans are to different types of messages received alongside the support for trade question – known as framing. While the results suggest strong support for more trade, the survey also showed considerable concern about potential job losses linked to more commerce and some messages could even alter the results.

In the experiment, respondents in 18 countries were randomly assigned to four experimental groups: control; positive framing; negative framing; and mixed framing. For instance, those in the positive framing group were asked, “Are you for or against (your country) increasing trade with other countries so that prices fall and the variety of products you may buy increases?” In contrast, respondents in the negative framing were asked: “Are you for or against (your country) increasing trade with other countries, even if increased trade causes employment losses in import competing sectors?”

The report says that, on average, negative framing decreases support for trade by 26 percentage points, from 73 percent to 46 percent.

“The impact of negative framing is similar to the combined impact of gender, education, ideology and media influence,” said the IDB’s Ernesto Stein, one of the lead investigators of the study. “Opinions can be swayed toward protectionism when common anti-trade arguments are used to frame the debate. Put another way, support is broad but not deeply rooted.”

While negative information has a sizeable impact, receiving positive information does little to increase support for trade, the experiment found. The group that received both positive and negative information also saw support for trade drop substantially, but by a smaller margin than for those who received only the negative framing. So, while positive information on prices and on the availability of new product varieties partially offsets the negative information on jobs, the combined effect is still strongly negative.

Framing impacts vary from country to country. Negative framing has little impact in Costa Rica, for instance, where attitudes to trade are firmer, perhaps due to the extensive public debate surrounding the 2007 CAFTA-DR free trade agreement referendum.

These results have important implications for policymakers. Trade reforms may bring positive results overall but almost inevitably there will be winners and losers. While the reforms may include measures to compensate losers, results of this study show that negative messaging on trade can easily influence how people think.

“People care mostly about employment when it comes to trade,” said the IDB’s Mauricio Moreira, the report´s co-editor and researcher. “Policymakers seeking to safeguard trade reform or to further liberalize their economies may need to counter any negative information with positive information about employment.”

“They may point to the potential employment opportunities that can emerge thanks to access to foreign markets, or the job losses that may result from losing such access,” he added.

About us

The Inter-American Development Bank is devoted to improving lives. Established in 1959, the IDB is a leading source of long-term financing for economic, social and institutional development in Latin America and the Caribbean. The IDB also conducts cutting-edge research and provides policy advice, technical assistance and training to public and private sector clients throughout the region.