The paradox in education: while education systems expand the use of technology to close learning gaps, more privileged environments prioritize learning centered on human development. The challenge is not whether to adopt technology, but how to design its use without compromising learning quality and equity.

When we talk about technology for education we think of tablets, laptops, robots or interactive platforms with which children learn new (coding) or traditional skills (mathematics) better or faster.

Raised like this, it seems inevitable to imagine that students or higher income schools have the most access to this type of resources. But, what would happen if access to technology in the coming years is not a privilege, but the cheapest way to access educational services?

Thus began an article recently published in The New York Times: "Hypocrisy thrives at the Waldorf School of the Peninsula in the heart of Silicon Valley. This is where Google executives send their children to learn how to knit, write with chalk on blackboards, practice new words by playing catch with a beanbag and fractions by cutting up quesadillas and apples. There are no screens — not a single piece of interactive, multimedia, educational content. The kids don’t even take standardized tests(...)".

Surprising, isn’t it?

Latin America and the Caribbean is investing more and more in technological equipment and digital resources to close the skills gap in the labor market and the learning gap between high and low income students.

By contrasting these efforts with the New York Times description of how the most privileged learn, it is worth wondering whether technology, after all, could potentially increase inequality in skills and learning.

One of the core objectives of education systems is to promote learning that prepares children and youth not only for the labor market, but also to contribute to create more prosperous societies. It is known that to access good jobs, a combination of technical skills and soft skills is required. This is nothing new. What is changing is the relative distribution of both. Although cognitive skills are still strongly related to results in the labor market (in terms of participation and income), their importance has been falling in the last two decades, while returns to soft skills have been increasing.

This trend is not accidental: to survive in the world of automation, it is a priority to teach young people what machines cannot do, because jobs that require imagination, creativity and strategy are more difficult to computerize.

An interesting fact comes from a study conducted by Google in 2013 to understand if their recruitment strategy focused on "hard skills" in computer science was appropriate. The results showed an uncomfortable reality: seven of the eight most important qualities shared by the highest-performing employees were soft skills such as being a good coach, communicating and listening well, knowing their colleagues well, empathy, critical thinking, problem solving, and connecting complex ideas. The technical competences in STEM fields came in last.

Faced with this boom of soft skills, learning to knit, write with chalk or practice new words while playing with balls are activities that go beyond a Silicon Valley fashion.

This type of education becomes a strategy to innovate, as the article in the New York Times said: "While Silicon Valley's raison d'être is to create platforms, applications and algorithms to generate maximum efficiency in life and work (a "frictionless" world, as Bill Gates once put it), when it comes to their own families (and also developing their own businesses), the new masters of the universe have a different sense of what it takes to learn and to innovate: it is a slow and indirect process, it is necessary to meander, not run, allow failure and chance, even boredom."

To close the skills gap in the region, we cannot forget the fundamentals behind this approach, but without losing sight of the fact that technological change comes at a galloping pace and offers new possibilities for children and young people.

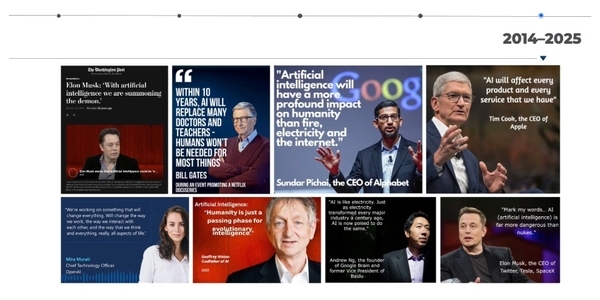

Today, the question that opens this article is no longer a simple provocation. The rapid expansion of artificial intelligence—capable of teaching, assessing, providing feedback, and personalizing learning at scale and at very low cost—is redefining what we mean by education and how it is delivered.

Educational technology is increasingly emerging as the most affordable and scalable way to provide educational services, especially in contexts marked by teacher shortages and limited resources. Automated tutoring, adaptive platforms, and AI-based assistants promise to expand access and close learning gaps. Yet this same promise carries a profound risk: that machine-mediated education becomes the norm for lower-income students, while more privileged settings continue to invest in deeply human educational experiences—rich in teachers, dialogue, critical thinking, art, philosophy, and time to learn without haste.

The paradox becomes clearer: the more sophisticated the technology, the greater the value of what is human. And that value is not distributed automatically or equitably. In a world where algorithms can deliver content, practice skills, and optimize learning pathways, the central question is no longer whether to use technology. The question is what kind of learning we reserve for whom. If technology is used to replace—rather than complement or enhance—the pedagogical relationship with teachers, vulnerable contexts risk drifting toward an even more stratified education system: automation for some, humanity for others.

The real challenge, then, is not to incorporate more devices, but to clearly define which learning experiences are non-negotiable for all. Educational innovation is not about cutting costs through screens, but about ensuring that technology amplifies—rather than substitutes—what makes learning profoundly human.

Because if the future of education offers teachers, books, conversation, and critical thinking for some, and algorithms, robots, and screens for others, technology will not have closed educational gaps—it will have institutionalized them.

In April 2025, the IDB released AI and Education: Building the Future Through Digital Transformation, a report that examines the role of artificial intelligence through the lens of what we already know from decades of digital education.

We invite you to explore the IDB’s latest report on Artificial Intelligence and Education, and discover how teachers across Latin America and the Caribbean are already integrating AI into their classrooms — based on new data from CIMA Note #37, drawn from the international TALIS 2024 survey.

*Note: This blog was originally published in 2018 and is being republished as part of an update to IDB content.