The COVID-19 crisis has impacted most aspects of social life in an unprecedented manner. And while the situation is nothing short of dramatic for the average person, the effects of the pandemic are felt far more acutely in prisons across Latin America and the Caribbean. More than 1.2 million people live behind bars in the region, most in overcrowded penitentiaries where poor conditions increase the risk of infection and governments struggle to find the appropriate response. In this first article of a two-part series, we discuss some of the challenges this crisis poses to the region’s criminal justice systems. Since the first case of COVID-19 was confirmed in Brazil in late February, the situation in Latin American prisons has been critical. Several riots have erupted not because of the virus itself but because of fear, uncertainty and poor communication between authorities and inmates. After the government restricted visitation rights in Brazil, 1.500 people escaped from prisons in Tremembé, Porto Feliz, Mirandópolis, and Mongaguá. In Colombia, prisoners staged riots in Bogotá and Huila that resulted in the death of 23 people and left 83 injured. Similar incidents have been reported within the last month in Argentina, Bolivia, the Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Panama, Peru, and Uruguay. Inmates are requesting better sanitation, flexibility with visiting schedules and concrete actions to decrease the risk of widespread infection. And some local governments have taken action to address their concerns. For example, a number of Mexican prisons have made visitations virtual by using videoconferencing technologies. Prisons in Jamaica and Argentina have increased access to disinfection and cleaning supplies and how often they clean cells and shared spaces. Meanwhile, countries like Chile and Brazil are currently evaluating laws that would release non-violent offenders over a certain age limit. Even though these measures are steps in the right direction, many of them lack coordination, have been poorly communicated, and vary drastically between countries.

Prisons in Latin America: High Incarceration Rate and High Occupancy Levels

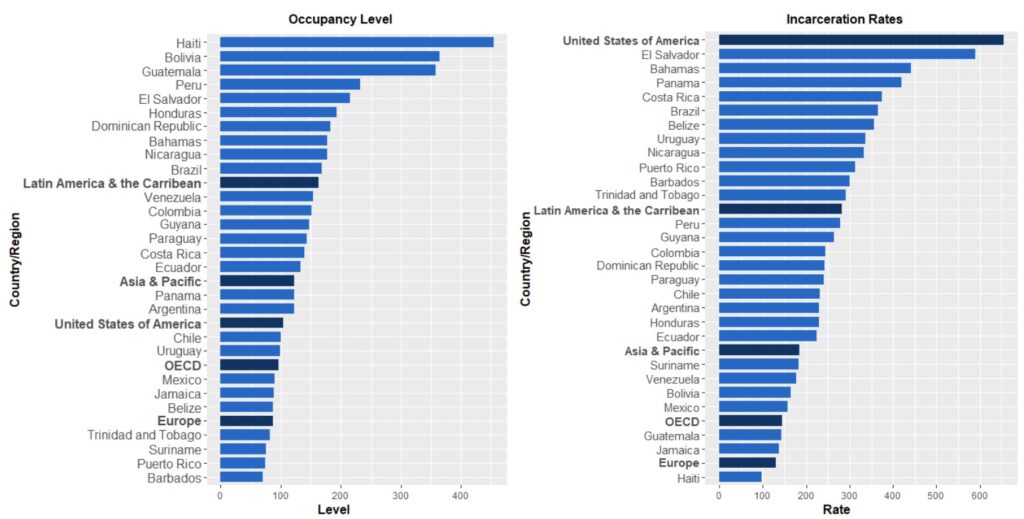

This pandemic has exacerbated the already chaotic situation in Latin American prisons. To really understand how vulnerable the region’s prison population is, we must first examine their situation before the novel coronavirus even hit. The Institute for Crime and Justice Policy Research (ICJPR) at the University of London pools data on prison populations and occupancy levels. According to their numbers, there are an average of 282 inmates for every 100,000 people in Latin America. In Europe, that figure drops to 130 inmates and in Asia and the Pacific to 184. Latin America is among the regions with the highest incarceration rates in the world, second only to the United States. At an average 163%, the region also has one of the highest prison occupancy levels. For every available unit in a Latin American prison there are currently 1.6 inmates. This figure climbs as high as 454% in the case of Haiti. In contrast, prisons in Europe have an average occupancy rate of 87%, with roughly half as many inmates per unit as in Latin America (see Figure 1). High incarceration rates coupled with high prison occupancy levels make for an environment where viruses and disease can spread easily. Immediate action is needed to contain this situation since countries like Colombia, the Dominican Republic, and Ecuador have already reported cases of COVID-19 in some of their prisons.Figure 1: Prison Occupancy Levels and Incarceration Rates for Selected Countries and Regions

Regional and OECD Averages in Bold. Source: Institute for Crime and Justice Policy Research

Several countries have already taken drastic measures to minimize the risk of contagion inside their prisons. As of April 20, a total of 5.925 federal and state-level inmates and 2.407 prison staff in the United States had tested positive, according to Covid Prison Data. States like New York, Ohio and Illinois have already released non-violent offenders in an effort to address overcrowding. Several countries in Europe and around the world have followed the same path. French, British and German authorities announced that they will be releasing 5,000, 4,000 and 1,000 non-violent inmates, respectively. France reported a decrease of 9% in its prison population between March 15 and April 1. Incidents similar to those reported in Latin American prisons have occurred in Italy and France. In response to the increased vulnerability of inmates, the United Nations Subcommittee on Prevention of Torture published a report this month detailing concrete steps for governments. Their recommendations center around ensuring the safety and health of inmates. The report also emphasizes the importance of providing accurate and complete information to inmates in a timely manner to avoid conflict. These recommendations reinforce inmate rights and liberties and are designed to limit the spread of the virus.