The widespread inequalities of economic opportunitiesin Latin America and the Caribbeanare a major concernforpolicymakers throughoutthe region. These inequalities are, in no small part, spatial. Where you live and where you work matters—often substantially—for your opportunitiesin life.Research is rapidly improving our understanding of the geographic dimension of inequality, and opening doors to new policy approaches to tackle it.

The recently published IDB reportThe Inequality Crisisshows thathousehold income and wages vary substantially across different subregions ofmany Latin American countries. Even in countries with relatively smaller spatial inequalities, such as El Salvador, the averagesalaryin the richest region is 40% higher than in the poorest. The gap is substantiallylarger in moregeographically-unequalcountries.For instance, in Argentina’sTierra del Fuegoregion,the average wagesare close to three times those in Santiago del Estero.Ten percent ofincome inequality across individualsfrom11 Latin American countries is explained by differences in average income across countries,and 7% by differences in average income across the main geographic regions within these countries. This is truedespite the fact thatmobility is not legally restricted within countries, unlike cross-border labor migration.While there is significant internal migration from low-opportunity to high-opportunity cities and regions, this appears to be insufficient to close the income per capita gap.

Even though inequalities across large subnational regions in Latin America are considerable, they pale in comparison to inequalitieswithin cities.For a closer look, Figure 1 decomposesBrazil’stotal wage inequality in 2010 by geographic level. Even though there are large income disparities across the five macro-regions of the country and across its 27 states, average wage differences across these geographies only account for about 1% of national wage inequality. Differences across cities within the same state, in turn, account for an additional 2%. But averagewage differences across neighborhoods within those cities explain about 9% of the country’s wage inequality.The distribution of within-city gaps tototal labor income inequalityin Brazil remainsdisproportionately highwhether we consider only human capital—that is, the fraction of wage differencesrelatedto schooling or experience—or only the component unrelated toworkers’observable human capital.

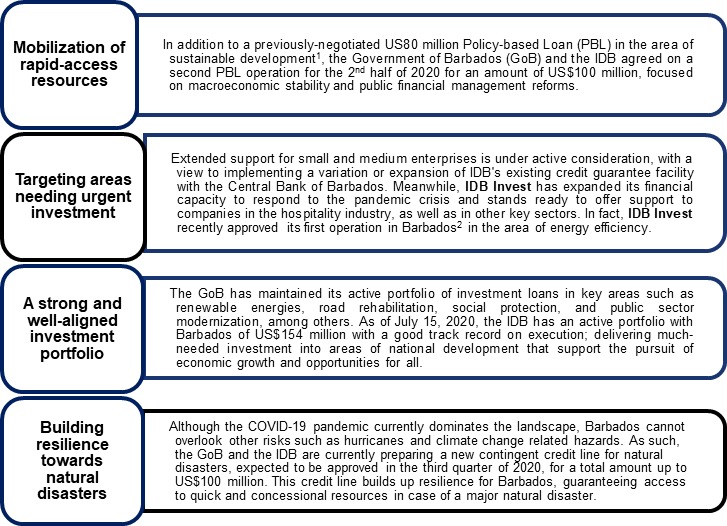

An even starker picture emerges when consideringdifferences in cost of living across localities.Thebottom panelof Figure 1shows the same geographic decomposition of inequality butadjustingnominal wagesby the average rentforeach city,which is typically a good approximation of overall cost of living.High-wage cities, where a large fraction of the country’s poorsettlein search of better opportunities, alsotend tobe expensive.Because housing costs represent a relatively larger share of the budget for low-income households, their real wagestend to be evenlowerthanforindividuals from high-income households.This holdsdespitethe significantresidential segregation generatedaslow-income households avoid the most expensive (and better connected) neighborhoods and,instead, settlein areas with more affordable housing.

Figure 1. Geographic Decomposition of Monthly Wage Inequality in Brazil, 2010

Source: MatíasBussoandJulián Messina (eds).2020.The Inequality Crisis: Latin America and the Caribbean at the Crossroads.

Source: MatíasBussoandJulián Messina (eds).2020.The Inequality Crisis: Latin America and the Caribbean at the Crossroads. Notes: IDB staff calculations using microdata from the population census in Brazil. Labor income is defined as the monthly wage in the main occupation. To adjust monthly wages for local cost of living and obtain a measure of real wage, the logarithm of the average housing rent in the city multiplied by 0.3 (the typical share of housing rents in the total income of renters) is subtracted from the logarithm of the individual monthly wage. In both the nominal and the rents-adjusted wage measures the top bar reports the labor income inequality of male and females between 16 and 65 years of age. The next two bars report the human capital and residual labor income inequality accounting for years of education and potential experience. See the report for further technical details on the decomposition.

HowSegregationLimitsAccess toEconomicOpportunities

Geographic segregation within cities, in turn, frequently acts as a barrier to economic opportunity.Notwithstandingcentrally locatedexceptions such as Villa 31 in Buenos Aires and favela Rocinha in Rio de Janeiro,low-income families in Latin America are disproportionallymore likelyto liveon the peripheryof a citythan high-income families. This makes access to centrally-located jobs more costly:Residentsof peripheral housing projects in citiesinBrazil, Colombia, and Mexico spend aroundtwice as much money and three times more timecommuting thanthose living close to the city center. This is in line with what researchers have found in the U.S., where workers are significantlyless likely to apply to jobsthat are more than ten miles from their residence andless likely to remain unemployedfollowing a mass layoff event if they live in better-interconnected neighborhoods.

Distance to job centers also plays a role in the persistently high levels of labor informality in Latin America. Figure 2 illustrates this using commuting time and informality data from Brazilian workers at different wage levels. The commuting patterns of formal and informal workers are strikingly different. Among workersfromthe formal sector, those with lower wages tend to commute more than those with higher wages.But among informal workers,the opposite is true: lower wages are associated with shorter commutes. This reflects the fact that low-wage informal jobs tend to be more dispersed across the geography of thecity, andare therefore moreaccessible to workers living far from central formal job locations. Similar patterns are observed inMexicoand other countries in the region.

Figure 2: Commuting Time and Informality by Labor-Income Level in Brazil, 2010

Source: MatíasBussoandJulián Messina (eds).2020.The Inequality Crisis: Latin America and the Caribbean at the Crossroads.

Source: MatíasBussoandJulián Messina (eds).2020.The Inequality Crisis: Latin America and the Caribbean at the Crossroads.Notes: IDB staff calculations using microdata from the population census in Brazil. The graph depicts the average commuting time of workers employed in the formal and informal sectors, along with the informality rates of each hourly wage percentile at the city level. The sample is composed of employed working-age individuals in 2010. Average commuting time is estimated based on midpoints of the time intervals available in the census. Informal workers are defined as those without a signed working card, excluding the self-employed.

Spatial inequality within cities not only affectsthe economic opportunities of workers today but also limits opportunities for future generations.A series of recent studies fromthe U.S.have found that growing upin a neighborhood with low vs. high economic opportunities makes a big difference in the long run.Children who movedto higher-opportunitycommunitiesas part of alarge government program showedsignificantly better outcomes as adults—including improved university enrollment, earnings, and single-parenthood rates.Other events leadingfamilies to relocate to better neighborhoods, such aspublic housing demolitionsin Chicago andhousing lotteriesin the Netherlands, have alsocreatedbetterfutureoutcomes forthechildrenwho relocated.

Policies toAlleviateSegregation-FueledInequality

Multiple policies addressingspatial inequalities have proved successfulatimprovingtheir beneficiaries’socio-economic well-being in the short run.For example, land titling programs have been linked to more years of schooling for children inArgentinaand increases in adultlabor supply inPeru.Slum upgradingprogramshave led to improved health outcomes inEl Salvador, Mexico, and Uruguay.And social housing programs have helped reduce the frequently severe housing deficits ofvarious countriesin the region.However, these policies have not necessarily helped reduce inequalities in access to economic opportunities.In some of these programs, initially positive effectsdisappear over time. This happenedinBrazil’sFavela-Bairro slums upgrading program, whereinfrastructure rapidly deterioratedand had fully reversed toitsinitial conditions 10 years later.In others, effortsto solve one problem can aggravate others.For example, social housingisfrequently builton the periphery of cities, where more and cheaper land is available.But beneficiaries of those programs tend to lose accessto jobs and the informal support of theirsocial networks.

Urban transportation projects appear to be particularly effective in tackling access to economic opportunities in segregated cities.Such projects have been linked to lower informality rates inMexicoandBrazil, better access to well-paying jobs inColombia, and greater employment and earnings for women inPeru.The experience ofTransMilenioin Bogota, however, shows that increased access to high-paying jobs for workersfromperipheral neighborhoods doesnot necessarily translate intolower spatialinequality. The increased labor supply to these job centers kept wages from growing, andgreaterhousing demand in neighborhoodswith improvedaccessibility pushed prices up andeventuallydisplaced lower-income households.This highlights the needforcomplementary policies that help preserve the initial inequality-reducing effects of transit and similar investments, such as zoning reforms that allow for greater housing supply in locations with better access to jobs.

Recent researchfromtheU.S.alsosuggeststhatlow-cost interventionssupportingfamiliesin their efforts to relocateto higher-opportunity neighborhoods may be effective.Anexperimental study randomly selected families fromapool of applicants to a housing voucher program in Seattle and provided themwithsupportinthe process of renting an apartment in high-opportunity neighborhoods—in addition tothe monthly rental assistance all beneficiaries received.This support included customized housing search assistance, short-term financial assistance to cover application fees and security deposits, and an insurance fund for landlords covering potential property damages.As a result of the intervention,a significantly higher share of familieschosehigh-opportunity neighborhoods (53% compared to 15% in the control group).One year later, these families were more likely to renew their leasesand report higher satisfactionlevelswith their neighborhoods.Studies like thishaveyet to be conductedin Latin America and the Caribbean, but if similar interventions also prove effective here, they could help expand our policy toolkitto reduce the pervasive inequality of economic opportunities in the region.