- Access gaps persist despite high enrollment: While primary completion is nearly universal, only 54% of young adults in Amazonia complete secondary education, compared to 69% nationally, with even larger gaps for Indigenous and rural students.

- Learning outcomes lag behind national averages: Students in Amazonian territories score up to 17 percentage points lower in reading, math, and science — equivalent to 6–7 months of lost schooling — reflecting resource constraints and limited curricular relevance.

- Structural and contextual barriers compound inequality: Long distances to schools, weak infrastructure, limited digital access, teacher shortages, and climate shocks interact to undermine continuity, quality, and equity in education.

Education is a fundamental right and a powerful lever for social mobility, health, and prosperity. In Amazonia, however, the promise of education is often unfulfilled. For millions of children and youth across the region, education is a daily struggle against distance, quality, and exclusion. Extreme heat is adding new pressure to these long-standing challenges.

At COP30, held for the first time in the Amazon region in 2025, the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) shared new evidence showing that many territories could face 70 to 80 school days per year above 26.7°C, the threshold at which heat begins to harm learning — putting millions of students across Latin America and the Caribbean at risk if no action is taken. By 2075, an estimated 195,000 schools, 15 million students, and 590,000 teachers across the region will be exposed to extreme heat without the capacity to cope. Even today, just 10 hot school days per year could translate into learning losses that reduce students’ future earnings by up to US$22 billion, underscoring the urgency of action.

This reality is the result of a unique set of structural challenges affecting the Amazon region and analyzed in our latest publication ‘Amazonia: A Journey Toward Resilience and Prosperity,’ published within the scope of the IDB Group’s Amazonia Forever regional coordination program, vast distances, scattered populations, inadequate infrastructure, a shortage of qualified teachers, and curricula that often fail to reflect local realities. These barriers are compounded by poverty, gender inequality, and the impacts of climate change, which disrupt learning and deepen existing gaps.

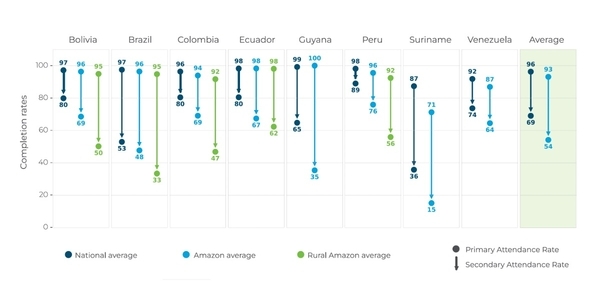

The numbers are stark. While primary school completion rates are nearly universal across Amazonian countries, the picture changes dramatically at the secondary level (Figure 1). On average, 69% of young adults (18–20 years old) in the eight Amazonian countries have completed secondary education, but in Amazonia, that figure drops to just 54%. The situation is even more critical for rural and certain population groups. Among Indigenous students, for example, secondary school completion is 14 points lower than that of their non-Indigenous peers.

Students in the Region have Lower Completion Rates than Students Outside the Region Living in the Same Countries

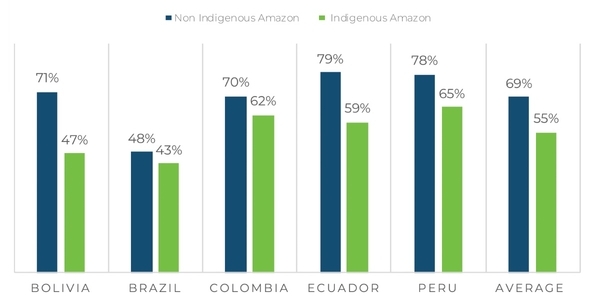

The situation is more critical in hinterlands and Indigenous territories. Data from Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru reveal differences between national averages and the Amazonian hinterlands of approximately 20 percentage points in secondary education completion rates (Figure 2). And among Indigenous students in the Amazonia Region, secondary school completion is 14 points lower than that of their non-Indigenous peers there.

Students Than Their Non-Indigenous Peers. Disparities in High School Completion: Amazonian Indigenous and Non-Indigenous Populations, Circa 2022.

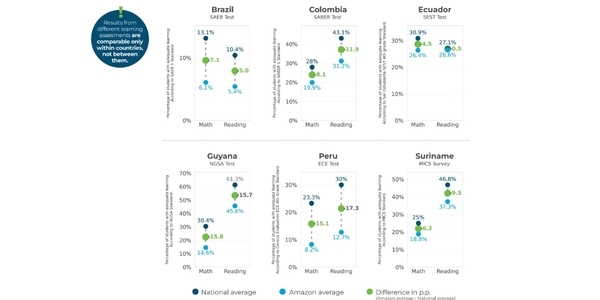

Learning outcomes are also a concern. National assessments in Brazil, Ecuador, Peru, and Suriname reveal differences of up to 17 percentage points between national and Amazonian averages in science, mathematics, and reading (equivalent to six or seven months of schooling). Indigenous students fare worse, with proficiency gaps of 12–13 percentage points in Suriname and Ecuador (Figure 3). These disparities reflect not only resource gaps but also a lack of culturally relevant curricula and teaching methods.

Gender disparities are pronounced, especially at the basic level and in illiteracy rates. In Ecuador’s Amazonia, the illiteracy rate for women is 4.2%, compared to 2.4% for men. In Colombia’s Amazonian departments, the gap is even wider: in Vaupés, 14.8% of women are illiterate versus 7.2% of men.

Achievements in Mathematics and Reading for Indigenous and Non-Indigenous.

- Late and interrupted schooling is a major factor behind low completion rates. Although age-appropriate enrollment rates are high (93% in Amazonia versus 95% nationally), many students fall behind or drop out. In Colombia, for example, seven out of ten school-age adolescents attend secondary school, but in more remote areas, it’s just five out of ten.

- Physical access to schools is a daily challenge for many students. Twenty-three percent of primary school-age children live more than five kilometers from the nearest school - over an hour’s walk. For secondary students, the figure rises to 29%. School transportation is available to only 12% of students in Amazonia, compared to 23% elsewhere. Many rely on boats or bicycles, making journeys slow and sometimes risky, especially during the dry season when riverboats may stop farther from home.

- School infrastructure is another major barrier. Access to electricity is lower in Amazonia than in other regions, and weather conditions — extreme heat, storms, floods, and droughts — often disrupt learning. Classrooms are frequently poorly ventilated and ill-equipped to handle high temperatures, which evidence shows can negatively affect cognitive performance and learning. This underscores the need to prepare schools to be heat-ready — able to function safely and effectively under high temperatures through adequate ventilation, cooling solutions, and basic services. Inadequate water and sanitation facilities further hinder attendance, especially for girls, who may miss school during menstruation due to lack of privacy or hygiene.

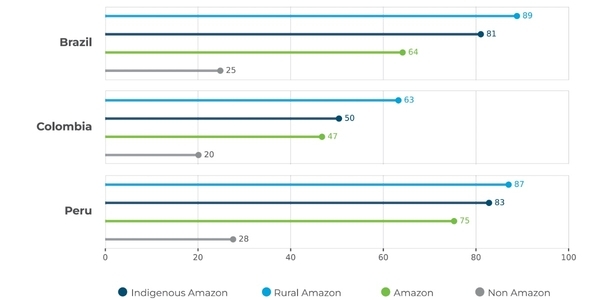

- Digital access is a growing divide. In Brazil, Colombia, Guyana, Peru, and Venezuela, school connectivity is lower in Amazonia than elsewhere. As seen in Figure 4, between 50% and 75% of schools in Amazonia lack computers or tablets for students, and in indigenous areas in Peru and Brazil, this figure can rise to 90%.

- Teacher shortages and low qualification levels are persistent problems, especially in Indigenous territories and remote areas. In Peru’s Amazonia, the percentage of teachers with university degrees in education is lower than in other parts of the country. In Brazil, only 9.4% of Indigenous teachers in the state of Amazonas have permanent contracts, compared to 85.3% in non-Indigenous schools. Attracting and retaining teachers in these areas is difficult, and temporary contracts exacerbate instability. There is also a lack of incentives — monetary or otherwise — to encourage teachers to work in challenging environments.

- Curricula often fail to reflect the realities and needs of Amazonian students. Environmental education is limited, despite the region’s central role in global climate and biodiversity. Only 19% of Latin American and Caribbean countries mention climate change in their educational plans. Yet, studies show that Amazonian students are highly interested in learning about local biodiversity and environmental issues. Technical and vocational education and training (TVET) is also underdeveloped, with lower enrollment rates in Amazonia than elsewhere, limiting pathways to green jobs and sustainable livelihoods.

Percentage of Schools Lacking Laptops, Desktops or Tablets.

Expanding climate-resilient, culturally adapted infrastructure is essential. Innovations like UrbanPy, an open-source tool for analyzing accessibility to urban services, can help governments identify where to build new schools. Ethno-engineered schools — designed with local materials and community input — offer models for sustainable, comfortable learning environments. Technology-mediated education, such as Brazil’s Media Centers and offline platforms like Kolibri, can bridge gaps in teacher availability and reach remote students, but require investment in connectivity and devices.

Improving teacher selection, training, and retention is critical. Scholarships and vocational guidance for local youth can help build a pipeline of teachers rooted in their communities. Monetary incentives, such as bonuses for working in remote areas, have proven effective in Chile, Peru, and Brazil, but must be carefully targeted and sustainable. Non-monetary incentives — housing, transportation, internet access — also matter. Training programs should prepare teachers for bilingual, intercultural, and climate-relevant education.

Developing students’ skills for sustainability is also a priority. Curricula should integrate environmental education, climate change, and local knowledge, empowering students as “green citizens.” TVET programs in areas like açaí processing, solar energy, and sustainable tourism can connect young people to emerging green jobs. Intercultural bilingual education is vital for Indigenous students, ensuring access to relevant, high-quality learning in their own languages and cultural contexts.

Education in Amazonia is not just about schools. It is about building resilient, inclusive communities capable of shaping their own futures. Only by advancing access, relevance, and resilience together can Amazonia unlock the potential of its people and secure a sustainable future for the region and the world.

Want to find out more? Download the publication Amazonia: A Journey Toward Prosperity & Resilience.

*Note: This blog is part of a joint analytical effort developed in collaboration with teams across the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB). It draws on and complements the evidence presented in Education in Amazonia: Why Access, Relevance, and Resilience Must Advance Together, with contributions from Gregory Michael Elacqua and Nadia Rocha.