- Latin America and the Caribbean may experience more supportive conditions for growth in 2026 due to improved financial conditions—driven by lower risk spreads—and stronger demand for selected exports.

- However, weak external demand and muted commodity prices, along with still tight global financial conditions, are likely to restrain investment and limit the contribution of trade and foreign capital to growth.

- Additionally, ongoing geopolitical conflicts, including in Ukraine and Venezuela, recent tariff policy decisions in the U.S., and persistent fiscal vulnerabilities are also weighing on the region’s growth prospects.

After a post-pandemic rebound, Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) appear to have reverted to a familiar pre-pandemic pattern, best described as modest growth. While early projections for 2026 are somewhat more favorable, the question arises as to whether this modest expansion could mark the beginning of a stronger growth cycle, or remain constrained by long-standing factors such as limited investment, continued reliance on external financing, and fiscal vulnerabilities.

This outlook is supported by positive growth outcomes across most economies, continued external demand for key exports, and better financial conditions, partly underpinned by fiscal consolidation efforts and lower risk spreads. However, how resilient this growth will prove in the face of global uncertainties and emerging risks linked to new trade policies, commodity prices, U.S. interest rates, and broader geopolitical volatility remains an open question.

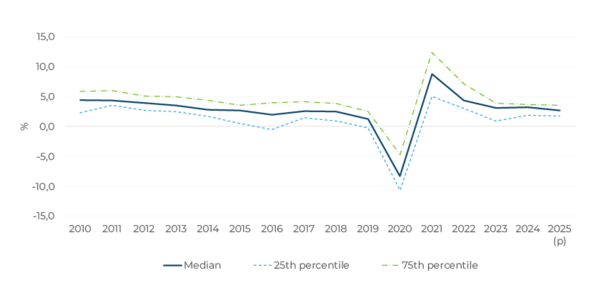

In both 2024 and 2025, economic growth in LAC settled back at around 2.5%, broadly in line with pre-pandemic rates (Figure 1). While most economies registered positive growth, often exceeding earlier expectations, the broader growth performance remains restrained.

Notes: (p) stands for preliminary. >The figure reports data for Argentina, Barbados, Belize, Brazil, Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Guyana, Haiti, Honduras, Jamaica, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Suriname, The Bahamas, Trinidad and Tobago, Uruguay, and Venezuela.

This lackluster outcome reflected the limited role of external trade and foreign investment in boosting regional growth, given slower growth in the United States and China in 2025. Global growth is estimated at 3.2%, below its pre-pandemic average of 3.7%. The United States grew by around 2%, China by 4.8%, and the European Union by 1.4%, all below their respective pre-pandemic rates of 2.4%, 7.7%, and 1.7%.

Commodity prices, another historical growth engine for the region, also failed to provide broad support. While the picture was mixed, oil and most agricultural commodity prices declined during the year (soybeans being a notable exception). In contrast, prices for copper and other metals linked to the energy transition increased, reflecting strong global demand. This benefited a small number of exporters, but the gains were concentrated and did not translate into a generalized regional upswing.

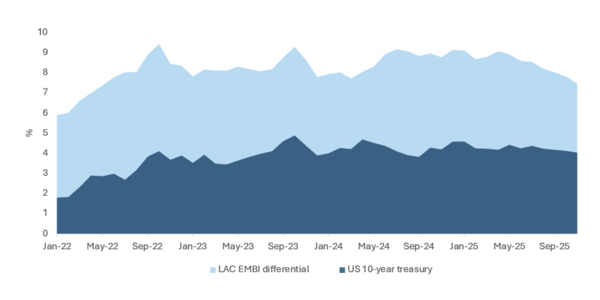

Global financial conditions further constrained growth. Financing costs remained significantly higher than in the past, nearly 2 percentage points above 2022 levels, which weighed on investment and growth (Figure 2).

What has changed, however, is the composition of those costs. Unlike previous years, when high spreads reflected elevated risk premia, recent increases have been driven mainly by continued tight monetary policy in the United States, as reflected in the base rate, the yield on 10-year U.S. Treasury bonds. Despite easing inflationary pressures in the United States and cuts in short-term interest rates, heightened uncertainty and rising perceptions of U.S. risk have kept long-term rates at elevated levels.

Notably, during 2025, risk spreads for LAC countries declined by more than 100 basis points on average, reflecting fiscal consolidation efforts across much of the region. The weakening U.S. dollar vis-à-vis regional currencies further bolstered fiscal positions.

These external headwinds not only weigh on growth through trade and financial channels; they also shape the way the region saves, invests, and finances itself. To understand why growth has remained so weak despite the post-pandemic rebound, it is useful to look beneath the headline numbers and examine how the composition of saving and investment has evolved across LAC.

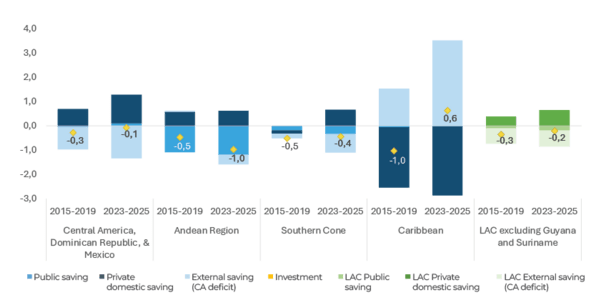

Recent growth dynamics are clearly reflected in the saving-investment decomposition shown in Figure 3. Between 2015-2019 and 2023-2025, most LAC subregions registered only modest improvements in public savings and, in some cases, a partial recovery in private savings. These gains, however, were more than offset by a pronounced deterioration in external saving, as current account deficits widened across the region. At the aggregate regional level, reliance on external financing intensified despite some improvement in domestic savings.

Notes: The Southern Cone includes Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Paraguay, and Uruguay. The Andean Region: Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, and Venezuela. The Caribbean: The Bahamas, Barbados, Guyana, Jamaica, Suriname, and Trinidad and Tobago. The Central America region includes Belize, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, and Panama. Estimates use simple country averages.

Crucially, this shift in the composition of saving has not translated into a sustained investment recovery. On the contrary, investment is expected to decline in the 2023-25 period, with especially large contractions in the Andean countries. In an environment of weaker external demand, less supportive commodity prices, and persistently high global interest rates, both reduced access to external savings and limited domestic savings have constrained capital accumulation. The Caribbean’s higher investment reflects improved fiscal positions and oil-related investments in Guyana and Suriname. But for the LAC region as a whole, growth has been increasingly driven by consumption rather than productivity-enhancing investment. This lack of investment growth helps explain in part why the region has reverted to its pre-pandemic pattern of modest growth and why medium-term growth prospects remain subdued.

The investment weakness and financing constraints described above help explain the region’s recent underperformance in growth. They also frame the question that matters most going forward: whether the external environment and domestic conditions will be supportive enough to break this pattern.

Looking ahead to 2026 and 2027, growth prospects appear somewhat brighter for the LAC region as a whole, but remain subject to unusually high uncertainty and disparities among subregions. Despite a rise in trade barriers with the United States in 2025 and a related increase in policy uncertainty, the markets project average GDP growth rates in LAC to exceed 3% in both 2026 and 2027, somewhat above the region’s average growth rate over the past 15 years (Figure 4).

Notes: The Southern Cone includes Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Paraguay, and Uruguay. The Andean Region: Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, and Venezuela. The Caribbean: Barbados, Guyana, Jamaica, Suriname, The Bahamas, and Trinidad and Tobago. The Central America region includes Belize, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, and Panama. The figure shows the simple average of GDP growth rates for each country group.

Prospects, however, differ markedly across the region: growth in the Caribbean is expected to be significantly boosted by the onset and continuation of oil booms in Suriname and Guyana, respectively. Meanwhile, continued strong global demand for metals and critical minerals is likely to support export growth in countries such as Chile, Peru, and Argentina.

That said, the global economy is entering largely uncharted territory. While the baseline outlook points to modest growth over the next two years, it rests on assumptions that remain fragile. The risks to the outlook are firmly tilted to the downside, reflecting a highly uncertain geopolitical environment that directly affects the region. In particular, there are significant risks surrounding commodity prices. Although ongoing conflicts, most notably in Ukraine and Venezuela, could lead to unstable spikes in key commodity prices, ample supplies and expected sluggish demand from China will likely keep prices subdued, weakening export revenues for several countries in the region.

Trade policy uncertainty also remains elevated. Ongoing domestic legal challenges to recent tariff policy decisions in the United States and shifting trade and geopolitical alliances could weigh on firms’ investment decisions in the region, further dampening already weak capital formation and growth.

In addition, recent signs of softening in the U.S. labor market could reduce external demand, with particularly significant implications for Central America and Mexico, given their strong dependence on the United States through trade and, in some cases, remittance channels.

Finally, fiscal vulnerabilities persist across much of the region. Borrowing costs could rise if long-term sovereign yields in major advanced economies remain high or increase further. Although lower spreads have offset this effect so far, this cushion may erode. At the same time, fiscal consolidation efforts have been modest in several countries, in some cases due to high interest rates, and could stall or reverse, given the political difficulty of sustaining reform coalitions, thereby adding another layer of risk to the medium-term outlook. How the region confronts these long-standing vulnerabilities may shape its capacity to navigate emerging uncertainties.

Keywords:

Economic Development