João knows every cracked sidewalk on his 9-mile trip to the building where he receives physiotherapy. Over the course of many journeys, he has memorized each irregularity, each dangerous intersection. Also engraved in his mind are the trees that line the streets, which he acknowledges with a hug: they help him measure the distance to his destination.

Due to his visual impairment, João is keenly aware of which traffic lights lack audible signals to tell him when to cross, or which bus stops pass unannounced.

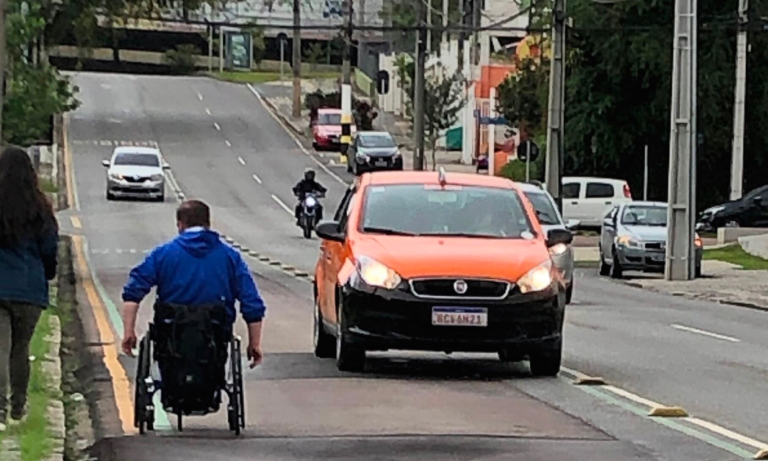

For Júnior, the routine of going to work carries different kinds of risks. With his wheelchair, each day he braves long stretches of road that lack a sidewalk, forcing him to push out onto the asphalt where trucks roar past him.

The dangers are different for Luciana, a student who returns home late from evening classes at her university. Concerns about harassment and gender-based violence condition her schedule and the way she dresses. If necessary, she picks itineraries that are winding and twice as long as normal to avoid walking through areas without public lighting.

João, Júnior, and Luciana are all users of the same public transport network in the city of Curitiba, in southern Brazil. Curitiba has long been an icon in urban mobility and sustainability, partly because of its pioneering development of a Bus Rapid Transit system that enables millions of people to traverse the city quickly and inexpensively. In recent years, however, this system has struggled with a lack of accessibility for differently abled people in a city with 300,000 residents who have a disability. And it has also seen rising levels of harassment, primarily of women who make up 61% of public transport users.

To address these problems and to increase passenger demand for public transportation, Curitiba is implementing an ambitious program to improve urban mobility with support from the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB). The project focuses on a stretch known as the Inter 2 Direct Line, which connects 28 of the 75 neighborhoods of Curitiba and serves an area that is home to 580 thousand people.

A Truly Inclusive Public Transport

In designing the program, officials in Curitiba and their counterparts at the IDB first set out to fully understand users’ needs. This meant getting insights from actual bus riders: IDB specialists and local officials traveled alongside commuters on their daily trips, talking to them and recording their experiences and needs.

"The Bank went and saw with its own eyes the difficulties, challenges, and barriers that these people face in their daily lives," says Lauramaría Pedraza, an urban planner for the IDB's Transportation Division. The program design incorporated insights and methodologies created by the Transportation Division, the Urban Development and Housing Division, and the IDB's Social Infrastructure Unit.

Two tools were used: the Customer Journey Maps - previously applied in Bogotá, Santiago de Chile, Medellín, and Santo Domingo - and the Gendered Walkability Index, to generate three diagnoses that helped to determine what is needed for inclusive transportation to be a reality in Curitiba.

In the Customer Journey Maps, the experience of the users is traced through twelve stages, each one meticulously identifying the physical, operational, communications, and attitudinal barriers they face, and recording the reactions and recommendations that they themselves formulate to achieve improvements.

"Sometimes the elevator access to the bus gets stuck,” explained Júnior during one stage.“ At those times, I have to ask for help, and the driver gets upset because it takes longer while the problem is solved."

Júnior's case was one of seven profiles chosen to reflect the plurality of experiences that the same journey can represent: those of a man with a physical disability, an elderly woman, a pregnant woman, a young woman with a cognitive disability, a young woman with a hearing disability, and a woman caring for her child. In each case, users were accompanied and listened to by a group of Bank experts and local officials.

“Disability is not a limitation,” says the IDB’s Pedraza. “The limitations emerge as barriers in the transport systems and urban space. This methodology helps us to understand the trip from the user's perspective.”

|  |

In addition to better access for people with disabilities, the team worked on learning about the experiences of women in public transport. In 2017, 37.1% of Brazilian women stated that they had been victims of harassment in the last 12 months.

“It is distressing to see how normalized harassment is,” says Amanda Beaujon, a gender consultant for the IDB's Infrastructure and Energy Sector. “A young woman reported that she had used public transport all her life, but one night, while she was returning home, a man harassed her. She began to feel unsafe during her commutes and decided to stop using public transportation.” Beaujon adds that migrating to other means of mobility is not an option available to everyone. “This reinforces inequality, because not everyone can afford it. Another user told us: ‘harassment is something I have to live with every day and I don't have a choice.’”

The second methodology used in Curitiba was the Gendered Walkability Index, a tool that assesses the quality of public spaces for pedestrians and considers the experience of women and girls when walking on the streets. The index was developed through questionnaires distributed over four daytime and nighttime routes by technical personnel from the Curitiba mayor's office, in partnership with the non-profit organization SampaPé.

The insights gleaned from these methodologies are now being used to plan a variety of upgrades and changes to Curitiba’s transportation infrastructure.

These changes can improve lives in measurable ways, from the time lost in longer routes that are perceived as safer, to the loss of jobs for individuals who cannot access a bus. According to a study by SampaPé, many women who live in Curitiba have rejected work or study opportunities due to commute lengths or because they want to avoid traveling at night. Changing this reality through infrastructure, including more route options, better lighting, and greater access to information, can open new avenues of opportunity.

“From the moment the first stone is laid, inclusion variables must be considered,” says Pedraza. “We had the opportunity to work on this project and the enormous satisfaction of incorporating these issues into this operation.”

*With the participation of Amanda Beaujon, Laureen Montes, Juliana de Moraes, Catarina Mastellaro, and Pablo Guerrero.

Learn more about accessibility and inclusion in Curitiba here (In Spanish).